Post #3 – The Bryde Bend – Readers Digest Version (as described in my email to UW Coach Pat Licari in 2004)

About four years ago, when Brad Walker was a senior at UW, I communicated with his coach Pat Licari for several months by phone and email. We discussed pole vaulting technique/models, and we analyzed some of Brad’s videos together – as well as some videos from other world class vaulters. Brad was on the phone with us on one of these calls. Pat expressed a lot of interest in my technique, and has implemented some drills with his UW vaulters that emphasize the trail leg lift. One of these is the high bar swinging drill. The trail leg lift is not a technique that suited Brad’s specific style, so there is no claim whatsoever that any of my technique has rubbed off on Brad. I think he’s doing just fine on his own!

This year, I had the pleasure of meeting Pat and some of his UW vaulters in person at a track meet in Eugene, and we continued our friendly discussions of my technique, Brad’s technique, and Jarred O’Connor’s technique.

For the benefit of Pat and the other UW vaulters, here’s how I described the Bryde Bend to Pat by email (and also by phone) four years ago. The ellipses represent the omission of personal details that don’t pertain specifically to the Bryde Bend.

Here's the email ...

… keeping the lead knee up and not pushing with the bottom hand are essential to my technique. … the importance of driving the chest through as far as possible. A bottom hand push would be counter-productive to this.

My run and plant were pretty standard stuff, except I used a high pole carry, which Shannon and I copied after watching Kjell Isaakson at the 1971 Portland Indoor. The logs (i.e. heavy poles) we used in those days presented a real problem with the weight of the pole dragging you down as you ran. These days, the sailed poles aren’t as heavy, but I think I’d still use the high pole carry, although I haven’t noticed any current vaulters using it.

I literally gained a foot in grip height and a resultant foot or so in clearance within a week after I changed my pole carry in the indoor 1971 season, moving my grip from about 14-0 to 15-0 – then eventually to 15-4, and increasing my PR from 15-0 to 16-4. Basically, as I rocked back for my first step, I raised the pole and reached both arms out in front of me, literally balancing the weight of the pole straight up and down, but slightly forward as I picked up speed.

The plant consisted of literally dropping the pole into the box, timed so that I never had to apply any pressure to align the pole to the box (it was always straight above/ahead), and so that I never had to hold it at any point during the drop. By this method, it felt literally weightless during the entire run & plant phases. I didn’t invent this; I just copied Isaakson’s pole carry technique.

I planted the pole “through the shoulder”, which is actually an impossibility, but is how I thought about it. A curl-plant (beside the shoulder) would put me off balance, and a forward plant would be – well – too far forward. So “through the shoulder” really meant just in front of the shoulder, but so close that it felt “through” the shoulder. I did lots of stretching/flexibility excercises every day, on the ground (sitting inclined, reaching arms behind me, and applying pressure) and on the rings, high-bar, and chin-bar (skin the cat, then stay in stretched position). These exercises also helped to drive the chest through, whilst the top hand stretched back – not a natural position without good shoulder flexibility.

My takeoff was also not much different than most other vaulters, I think, except that I probably had a taller, more aggressive takeoff than average. I rationalized that all the speed gained down the runway (which I didn’t have much of) was only a setup to speed on takeoff, so I could gain a slight advantage by a strong takeoff.

… What really matters is velocity on TAKEOFF. Nothing else matters! Even your speed 2 strides out is only a setup for your TAKEOFF speed!

Shannon and I worked on striking the takeoff like a long-jumper, with acceleration – not braking. Despite my lack of speed, I was a fair long-jumper & triple-jumper in high-school – nothing spectacular but good enough to win most district meets, and to place in the BC High School Meet in triple jump. And I could dunk a volleyball (not a basketball – couldn’t grip it!), so at 6-0 I had pretty good spring, which I used in my takeoff – jumping forwards at maybe 20 degrees, not up.

The best takeoff drill, useful even in competition warm-ups, was to takeoff and forward roll into the pit. I combined this drill with checking my steps. Using my normal runway marks, I never had a problem in reaching the pit, although I wouldn’t recommend this to novice vaulters.

We often practised vaulting … with a 9-step run. My best was 15-9, with a 13-8 grip. With that low of a grip, and with that short of a run, pole carry wasn’t an issue. But 9-step vaulting forced me to emphasize a strong, aggressive takeoff. It was impossible to build up much speed in 9 steps, so the takeoff HAD to be quick! And short runs actually allowed us to get a lot more vaults in per day. I rarely practised full vaults with a long run, and when I did, I rarely went much higher than 16-6. I was very much a competition vaulter – I needed to get the juices flowing to vault well. And in competition, I found that I knew when I would make or break the height, based on how my takeoff felt, because my technique once I left the ground was quite consistent.

OK, we’re finally to the innovative part of my technique!

First, I’ll reference the definition of “follow-through” from the US Pole Vault Education Initiative’s “Pole Vault Vocabulary” webpage:

http://www.pvei.com/index.php?pagename=art-vocab.php FOLLOW-THROUGH – is a short phase during the vault, where the vaulter’s hips and chest follow through in a forward upward direction. The hips and chest should follow through in a linear fashion rather than having the hips rotate around the shoulders. As the hips and chest are following through, the arms and takeoff leg drag back and behind the vaulters body. The follow-through prevents an early swing-up action after takeoff.

This definition of this phase of the vault is actually very close to my technique, with one critical exception. Instead of passively letting the “takeoff leg drag back and behind”, I literally stretched my trail leg back and UP!

We referred to this as “jump-to-the-split-position”, because that’s literally what I did. I took off the ground like a long-jumper, but raised my lead knee forwards and my trail leg backwards into an exaggerated “split” position. Today, they refer to it as the “C” position, but make no mention of purposely raising the trail leg.

To my knowledge, no one else even attempted to pause in the C position in my era, let alone raise the trail leg. I don’t know what year the “follow-through” phase was defined, but I really think that as vaulters started going higher (18’+), this became more and more of a distinct phase. … When I did 9-step vaults, the rhythm of the vault was of course much quicker, and most vaulters that only did 15-9 with a full run would not even see the need for raising the trail leg before starting the swing. But I consciously did this, even though the entire rhythm was sped up. I don’t think I could have cleared 15-9 with 9 steps without a very aggressive swing, which came from the aggressive takeoff and raising the trail leg before whipping it downwards and forwards.

I mention the issue of the practicality of jumping 15-9 with my technique to show that it’s something that’s definitely applicable to women’s vaulting at even that low height and low grip, even though it’s less of an issue than when vaulting 17’+. …

By whipping, I’m referring to the action of starting the whip from your chest, then down your gut muscles to your hips. The slow part of the whip is your torso straightening out (transforming your torso from a “C” to an “I”), and then the fast part of the whip is snapping the trail leg (and upper arm – but mostly trail leg) until your entire body is straight (top hand, chest, hips, and trail leg aligned, lead knee still up). It’s easier to demonstrate on a chinning bar than to explain, but I hope you catch the essence of what I mean.

During the whip, you refrain from rowing with your arms, but you do use a forwards lever action to return your top arm from the C-position to the torso I-position. Once you’re past the pole, you can row all you want, but you don’t really need to, because you already have all the rotational momentum that you need to rock back. Muscle vaulters row – gymnastic vaulters (like me) swing. Swinging is much easier, and more efficient according to the laws of physics. (I learned this from watching the UW gymnasts on high bar and rings. The best gymnasts didn’t use their muscles – they used the leverage in their limbs, timed just right for each trick. A kip-hip-circle-shoot-to-a-handstand is the most applicable example of this.)

OK, that’s my innovative technique, but I haven’t yet told you WHY I wanted to do that. Some people thought I was just trying to bend the pole more. Well – I was, but WHY? Steel vaulters used to use a double-pendulum technique, where their top hand was the fulcrum of one pendulum, whilst the butt of the pole was the other fulcrum. Speed vaulters (the name I gave to vaulters that relied on their runway sprint speed to flip them upside down and over the bar) roughly followed this steel vaulting technique. My observation of them was first that I’d never beat them at their own game, and second, that they never had enough time to get upside down into a position where they could aggressively shoot skywards. They seemed happy with their “quick-bend” technique, but in my opinion they didn’t apply any extra energy into the pole after takeoff.

I wanted to be already upside down by the time the pole started recoiling. If I was upside down, then I could shoot skywards aggressively. I wanted to shoot past vertical – meaning that instead of shooting straight up, I could aim slightly AWAY from the bar, back towards the runway, and my forwards momentum added to this would shoot me vertically. I of course needed to have good forward momentum to achieve this, but in my best vaults, I did shoot past vertical. If I didn’t, I would have shot under the bar. And I did this in a continual, fluid motion, starting from just after I passed the pole.

I landed well into the pit (standards set at 24”) on my best vaults. In my accidents (1969-1970) where I landed on the edge of the box, I had actually already aborted a bad takeoff, so never got to the point of extending. I hadn’t even learned my new technique yet.

The “Big-Bend” was just what spectators saw, because I delayed the recoil longer than “quick-bend” vaulters. But for me, it was just the means to the end goal of getting upside down earlier in the vault. It’s easy to big-bend a soft pole, but that doesn’t do you much good. Soft bend = soft reflex. My best jumps were on 190# and 195# SKY-POLES, gripping at 15-4, and weighing 173. Definitely not a soft bend!

As I said earlier, after lifting my trail leg and keeping it straight, I whipped it down in a swinging action, starting at the chest, but finally hinging at the hips. This was no ordinary swing. I swung as hard and as fast as I could. Because I stayed tall, driving my chest forwards while raising my trail leg, I was through to the point at which my top hand, hips, and trail leg were all aligned well before I “passed the pole” (the imaginary line between the top hand and the pole butt).

I mentioned a couple pundits earlier, who say that the bar clearance can basically be computed by taking your takeoff speed and applying it to a mathematical formula.

Other biomechanics add that pole vaulting is a matter of velocity on takeoff + energy exerted after takeoff. This kinetic energy is transformed into potential energy in the pole, and gets released back to kinetic energy when the pole recoils.

Well, … they missed a slight detail. Once you leave the ground, there’s TWO distinct parts of the vault where you can gain more altitude – first adding potential energy into the pole during the swing – as I just described – and second whilst the pole is recoiling!

You now know the first part – finalized by the whipping action – much like a football place kicker, except way more vigorous. I could whip my trail leg more vigorously, because it was further back than most other vaulters, and because I did specific speed drills (on the chinning bar and the high bar) to improve my gut strength and speed for this. A side effect of this delayed whipping action was the “Big-Bend”.

The second part was the easy part. My trail leg speed not only drove more energy into the pole, but it also set me up to rotate faster to a rockback. This action initiated BEFORE passing the pole. As the pole “bounced” at maximum bend, I was dropping my shoulders and raising my hips. That put me in a good position to extend past vertical as vigorously as I wanted, in an upwards/backwards direction over the top of the pole.

Other vaulters often told me that it always looked like I was going to sink under the bar, but at the last split second I shot straight up! My trail leg didn’t tuck much at all. It didn’t have to, as I was already extending out of my rockback just as the pole was straightening.

I think you can appreciate the advantage of extending in unison with the pole recoil, so I won’t go into detail about it. To me, this felt exactly like the “clean” part of a “clean and jerk”, where you used your back and not your arms. Also quite similar to a kip-hip-circle-shoot-to-a-handstand on high bar.

Kirk Bryde

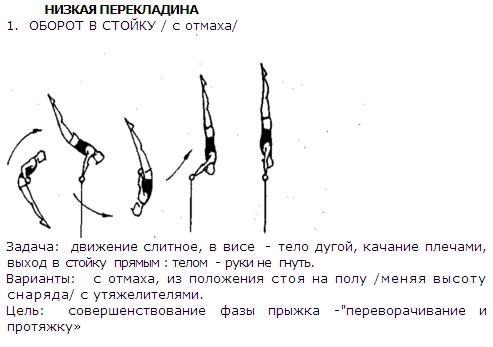

EDIT: I mentioned the hip-circle-to-a-handstand twice in this post, so here's a visual explanation of it ... from a Russian gymnastics manual that Pogo Stick published here

http://www.polevaultpower.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=30&t=18899&p=135360#p135360 today ...

- Hip-Circle-to-Handstand (Russian).JPG (28.23 KiB) Viewed 36242 times

So maybe you could help me understand better/more simply how your technique differed from Bubka's? I'm really looking forward to exploring this thread more once I've got the time...

So maybe you could help me understand better/more simply how your technique differed from Bubka's? I'm really looking forward to exploring this thread more once I've got the time...